VMDO Architects, 2013. The new carter G. woodson center education complex located in Buckingham county, in central, rural Virginia, has been designed and renovated as a modern learning campus for K–5 students with the intent to promote connectivity, creativity, physical activity, health and well-being for students and for the Buckingham county district community. The design for the school renovation was developed using novel theory-based guidelines created collaboratively by the design team and health research teams from the university of Nebraska and the university of Virginia. the project involved renovating two former schools built in 1954 and 1962, and connecting them through newly built structures to form one new school. the architectural firm VMDO oversaw and supported the designs for architecture, interior spaces, graphics and wayfinding, and landscaping.

Tag: Healthy Schools

Healthy Eating Design Guidelines for School Architecture

Terry T-K Huang, PhD, MPH, CPH; Dina Sorensen, MArch; Steven Davis, AIA; Leah Frerichs, MS; Jeri Brittin, MM; Joseph Celentano, AIA; Kelly Callahan, AIA; Matthew J. Trowbridge, MD, MPH, 2013.

We developed a new tool, Healthy Eating Design Guidelines for School Architecture, to provide practitioners in architecture and public health with a practical set of spatially organized and theory-based strategies for making school environments more conducive to learning about and practicing healthy eating by optimizing physical resources and learning spaces. The design guidelines, developed through multidisciplinary collaboration, cover 10 domains of the school food environment (eg, cafeteria, kitchen, garden) and 5 core healthy eating design principles. A school redesign project in Dillwyn, Virginia, used the tool to improve the schools’ ability to adopt a healthy nutrition curriculum and promote healthy eating. The new tool, now in a pilot version, is expected to evolve as its components are tested and evaluated through public health and design research.

Insights on Childhood Obesity and School Design

Terry Huang, Matthew Trowbridge, VMDO Architects

THE DINING COMMONS represents a new direction in design research; architects, public health researchers, educators, and VS come together to examine one of the most complex environmental health issues of our time: childhood obesity. This design-research partnership marks a powerful moment in the design of learning environments as experts from disparate yet interrelated disciplines engage with the problem of childhood obesity by seeking to understand the political, social, economic, ecological, and infrastructural agendas that make up the school food environment. The DINING COMMONS highlights design strategies implemented at the Carter G. Woodson Education Complex in Buckingham County, VA. This K-5 campus project was completed in Summer 2012 with the aim of promoting healthful eating and physical activity with a particular emphasis on the design of indoor and outdoor dining, teaching / activity spaces, and connectivity with the larger community. Follow-up studies will be conducted by academic institutions from across the country.

Healthy Eating Design Guidelines for School Architecture

University of Virginia, University of Nebraska Medical Center, VMDO Architects. Information provided in this link deal with concerns about providing a well designed space that promotes healthy eating for students.

School Facility Health, Safety, and Security Can Affect Student Motivation and Achievement

By Angel Ford, February 6, 2015.

Citizens that care about students might come to a consensus that safe and healthy school buildings are an important consideration of education. According to Webster’s Dictionary, safety is “the condition of being safe from undergoing or causing hurt, injury, or loss,” and healthy is “good for and conducive to health” (Merriam-Webster).

When including safety and health into an effective definition of school design, it would mean to plan and make decisions about school facilities (both in new construction and existing buildings) to ensure students, teachers, staff, and visitors will be safe from hurt, injury, or loss and will be in an environment that is good for their health.

We wouldn’t knowingly send children into structurally unsafe buildings with crumbling roofs or walls that are falling down; however, some conditions that affect health and safety are less obvious such as poor indoor air quality and/or mold, toxic building materials from years ago or in some instances inadequate climate control

Some schools have elements that are in need of repair and some even have elements that are beyond repair. This should not be the case. We need to do better for our students. Parents should be confident that the buildings where their children learn are designed or redesigned in line with best practices for safety and health.

Outside of the initial concerns for safety and health is the idea that these poor conditions can affect student motivation and thus student achievement.

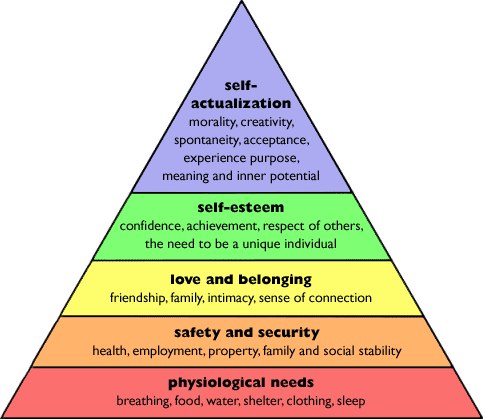

Maslow’s theory of motivation shows it is important to ensure that people are in environments that meet basic human needs, with the physiological (health) needs and the need for safety being foundational (Maslow, 1943).

Meeting these basic needs does not guarantee that students will be motivated to learn; however, any area where educators can remove known obstacles the path to learning is more likely. When basic needs are not met, “The urge to write poetry… the interest in American history… become of secondary importance.” (Maslow, 1943, p. 3).

If the basic needs of students are not being met, then time and energy must be used tending to those needs before time and energy can be spent on academics. If students are too cold or too hot, they may not be able to focus (Earthman, 2004; Uline & Tschannen-Moran, 2007 ). If the classroom is not well lighted, is overcrowded or unsafe in anyway, the focus of the students may not be on the lessons (Uline & Tschannen-Moran, 2007). If a building even feels unsafe to the students because of broken fixtures, graffiti, etc., the students may be unable to concentrate on the academic goals in front of them.

Looking at the importance of school environments through the lens of Maslow’s theory of motivation, there may be some evidence that without meeting basic needs it could be difficult for students to make an effort to concentrate their attention on developing academic patterns and digesting the academic materials they are being presented.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Schools in poor conditions have the potential to affect student achievement through changing students’ moment to moment motivation. Students shouldn’t be in survival mode. If they are, we cannot expect them to thrive.

Keeping the work of Maslow in mind, designing and maintaining schools for safety and health must be high priorities. These are the most basic needs of our students and crucial to their learning environment.

Keep following The Educational Facilities Clearinghouse (efc-staging.edstudies.net) as we expand our information on Safety by Design for schools. The motivation and academic achievement of students depend on having physical environments conducive to learning.

Printable Blog Post

References

Earthman, G. I. (2004). Prioritization of 31 criteria for school building adequacy. Baltimore, MD: American Civil Liberties Union Foundation of Maryland.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

Uline, C. & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2007). The walls speak: The interplay of quality facilities, school climate, and student achievement. Journal of Educational Administration, 46(1), 55-73.

http://www.researchhistory.org/2012/06/16/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs/

Angel Ford is a research assistant with Education Facilities Clearinghouse, where she is actively involved in research and content management of the EFC Website. She is also pursuing her Doctorate in Education with her dissertation topic to be in the area of educational facilities.

The Princeton Review’s Guide to 332 Green Colleges (2014)

More and more students are going to college now than ever before, so educational institutions are busy accommodating this growth with new academic buildings and dorms while ensuring that existing facilities are running efficiently. The U.S. Green Building Council's (USGBC) LEED® green building program) helps provide a layer of accountability for college campuses seeking ways to make their green building projects, both old and new, as environmentally responsible as possible. LEED, or Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, is a globally accepted benchmark for the design, construction, and operation of green buildings. Many of the schools profiled in these pages have LEED-certified buildings on campus or a commitment to future LEED projects, but that was not a criterion for inclusion in the book.

All of the schools in this guide, whether or not they are profiled in our annual Best Colleges book, are exemplary institutions that address the balance of people, planet, and prosperity in fascinating ways. Our hope, in coordinat- ing with the USGBC and its Center for Green Schools, is to break down what green looks like across different campuses in a way that will help you to choose the right school to live sustainably.

Do attributes in the physical environment influence children’s physical activity? A review of the literature

Kirsten Krahnstoever Davison and Catherine T Lawson, 2006. Background: Many youth today are physically inactive. Recent attention linking the physical or built environment to physical activity in adults suggests an investigation into the relationship between the built environment and physical activity in children could guide appropriate intervention strategies.

Method: Thirty three quantitative studies that assessed associations between the physical environment (perceived or objectively measured) and physical activity among children (ages 3 to 18-years) and fulfilled selection criteria were reviewed. Findings were categorized and discussed according to three dimensions of the physical environment including recreational infrastructure, transport infrastructure, and local conditions.

Results: Results across the various studies showed that children's participation in physical activity is positively associated with publicly provided recreational infrastructure (access to recreational facilities and schools) and transport infrastructure (presence of sidewalks and controlled intersections, access to destinations and public transportation). At the same time, transport infrastructure (number of roads to cross and traffic density/speed) and local conditions (crime, area deprivation) are negatively associated with children's participation in physical activity.

Conclusion: Results highlight links between the physical environment and children's physical activity. Additional research using a transdisciplinary approach and assessing moderating and mediating variables is necessary to appropriately inform policy efforts.

National Study of Changes in Community Access to School Physical Activity Facilities: The School Health Policies and Programs Study

Kelly R. Evenson, Fang Wen, Sarah M. Lee, Katie M. Heinrich, and Amy Eyler, 2010. The purpose of this study was to describe the prevalence of indoor and outdoor physical activity facilities at schools and the changes in prevalence of the availability of those facilities to the public in 2000 and 2006. Secondarily, we sought to determine whether the availability of these facilities differed by several potential correlates. This will help determine if progress is being made toward the Healthy People developmental objective and provide some guidance for school-level interventions.

Prevalence of School Policies, Programs, and Facilities That Promote a Healthy Physical School Environment

Sherry Everett Jones, Nancy D. Brener, and Tim McManus, 2003. The physical environment in schools is receiving increased national attention. Several federal efforts to improve school environments have been implemented during the past 5 years. In 1997, President Clinton created the Task Force on Environmental Health Risks and Safety Risks to Children. On April 18, 2003, President Bush signed an executive order to extend the work of the task force through 2005. Cochaired by the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency and the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, the task force is charged with identifying and developing federal strategies to protect children from environmental health threats.

In October 2001, the task force created a Schools Workgroup to explore ways for federal departments and agencies to expand cooperation to improve school environmental health. The Schools Workgroup’s goals are to improve children’s health and school performance by making existing and new schools healthier places to learn, and to ease the burden on underfunded and overextended school districts and schools by improving coordination and collaboration among federal, state, and local programs.

Characteristics of School Campuses and Physical Activity Among Youth

Angie L. Cradock, Steven J. Melly, Joseph G. Allen, Jeffrey S. Morris, Steven L. Gortmaker, 2007. Previous research suggests that school characteristics may influence physical activity. However, few studies have examined associations between school building and campus characteristics and objective measures of physical activity among middle school students.

Students from ten middle schools (n=248, 42% female, mean age 13.7 years) wore TriTrac-R3D accelerometers in 1997 recording measures of minute-by-minute physical movements during the school day that were then averaged over 15-minute intervals (n=16,619) and log-transformed. School characteristics, including school campus area, play area, and building area (per student) were assessed retrospectively in 2004–2005 using land-use parcel data, site visits, ortho-photos, architectural plans, and site maps. In 2006, linear mixed models using SAS PROC MIXED were fit to examine associations between school environmental variables and physical activity, controlling for potentially confounding variables.