By Angel Ford, February 6, 2015.

Citizens that care about students might come to a consensus that safe and healthy school buildings are an important consideration of education. According to Webster’s Dictionary, safety is “the condition of being safe from undergoing or causing hurt, injury, or loss,” and healthy is “good for and conducive to health” (Merriam-Webster).

When including safety and health into an effective definition of school design, it would mean to plan and make decisions about school facilities (both in new construction and existing buildings) to ensure students, teachers, staff, and visitors will be safe from hurt, injury, or loss and will be in an environment that is good for their health.

We wouldn’t knowingly send children into structurally unsafe buildings with crumbling roofs or walls that are falling down; however, some conditions that affect health and safety are less obvious such as poor indoor air quality and/or mold, toxic building materials from years ago or in some instances inadequate climate control

Some schools have elements that are in need of repair and some even have elements that are beyond repair. This should not be the case. We need to do better for our students. Parents should be confident that the buildings where their children learn are designed or redesigned in line with best practices for safety and health.

Outside of the initial concerns for safety and health is the idea that these poor conditions can affect student motivation and thus student achievement.

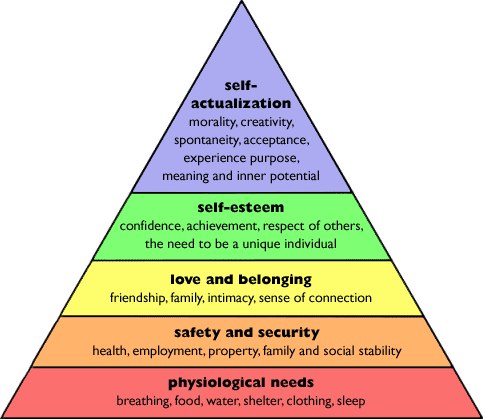

Maslow’s theory of motivation shows it is important to ensure that people are in environments that meet basic human needs, with the physiological (health) needs and the need for safety being foundational (Maslow, 1943).

Meeting these basic needs does not guarantee that students will be motivated to learn; however, any area where educators can remove known obstacles the path to learning is more likely. When basic needs are not met, “The urge to write poetry… the interest in American history… become of secondary importance.” (Maslow, 1943, p. 3).

If the basic needs of students are not being met, then time and energy must be used tending to those needs before time and energy can be spent on academics. If students are too cold or too hot, they may not be able to focus (Earthman, 2004; Uline & Tschannen-Moran, 2007 ). If the classroom is not well lighted, is overcrowded or unsafe in anyway, the focus of the students may not be on the lessons (Uline & Tschannen-Moran, 2007). If a building even feels unsafe to the students because of broken fixtures, graffiti, etc., the students may be unable to concentrate on the academic goals in front of them.

Looking at the importance of school environments through the lens of Maslow’s theory of motivation, there may be some evidence that without meeting basic needs it could be difficult for students to make an effort to concentrate their attention on developing academic patterns and digesting the academic materials they are being presented.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Schools in poor conditions have the potential to affect student achievement through changing students’ moment to moment motivation. Students shouldn’t be in survival mode. If they are, we cannot expect them to thrive.

Keeping the work of Maslow in mind, designing and maintaining schools for safety and health must be high priorities. These are the most basic needs of our students and crucial to their learning environment.

Keep following The Educational Facilities Clearinghouse (efc-staging.edstudies.net) as we expand our information on Safety by Design for schools. The motivation and academic achievement of students depend on having physical environments conducive to learning.

Printable Blog Post

References

Earthman, G. I. (2004). Prioritization of 31 criteria for school building adequacy. Baltimore, MD: American Civil Liberties Union Foundation of Maryland.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

Uline, C. & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2007). The walls speak: The interplay of quality facilities, school climate, and student achievement. Journal of Educational Administration, 46(1), 55-73.

http://www.researchhistory.org/2012/06/16/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs/

Angel Ford is a research assistant with Education Facilities Clearinghouse, where she is actively involved in research and content management of the EFC Website. She is also pursuing her Doctorate in Education with her dissertation topic to be in the area of educational facilities.