By Dr. Linda Lemasters.

In 1973 Thurgood Marshall wrote the dissenting opinion in San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez:

It is an inescapable fact that if one district has more funds available per pupil than another district, the former will have greater choice in educational planning than will the latter. In this regard, I believe the question of discrimination in educational quality must be deemed to be an objective one that looks to what the State provides its children, not to what the children are able to do with what they receive. That a child forced to attend an underfunded school with poorer physical facilities [emphasis added], less experienced teachers, larger classes, and a narrower range of courses than a school with substantially more funds—and thus with greater choice in educational planning—may nevertheless excel is to the credit of the child, not the State. Indeed, who can ever measure for such a child the opportunities lost and the talents wasted for want of a broader, more enriched education?

Though written 42 years ago, we continue to face many of the same disparities. I wrote about educational disparities a few months ago, but I would like to be more specific in my concerns. As a college professor in educational leadership, hardly a day goes by that an article, a conference announcement, an email, or a piece of research comes across my desk about the achievement gap. The gap is a real detriment to our country with a waste of talent, and immeasurable in its affect on our society.

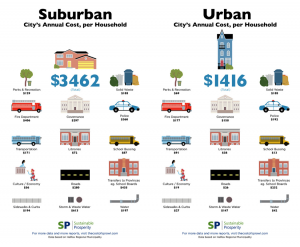

In the same articles, email, or research, varied solutions are proposed. Nearly all of them go back to the genesis of teaching, leadership, technology, supplies, class size, and/or many other suggestions, and some, if not all, of these factors may be interrelated. Sad to say, there is only a small group of educators in America who relate some of the achievement gap to where our children learn. There is even a more select group that conducts research relating the gap to the condition of the schools. The schools in most need of repair are often those who report lower overall achievement scores. These schools are found in the poor areas of our cities, towns, and rural districts and are disproportionately attended by severe low-income and minority students.

The question is: Are these facilities contributing to the achievement gap? The Education Facilities Clearinghouse recently commissioned C. Kenneth Tanner, Professor Emeritus, University of Georgia, to conduct a meta-analysis of effects of school design on student success. He was able to identify best practices in schools and school design:

- Safety and security measures, as defined by Tanner’s meta-analysis, have a statistically significant impact on student outcomes.

Students need to feel free from gangs, hunger, intruders, violence, social disparities, and persecution. As Maslow’s hierarchy indicates, humans need to feel secure and have a sense of belonging, safety, and confidence. Have you noted inner city schools in which the very physical setting alarmed your sense of safety and security?

- Quiet places and spaces for reflection have a statistically significant influence on student outcomes.

Students need places that make them feel they are needed and belong in the school environment. Again, Maslow wrote about self-actualization and its dependence on both belonging and a place for reflection. All children need small personal learning spaces, alcoves to read, and small group spaces for interaction in safe, dry, and clean facilities. In poorly funded districts, overcrowding and inadequate facility maintenance are more often the reality.

- Color is statistically significant in its effect on student achievement.

Tanner (2015) wrote: “Color patterns throughout the facility can influence motivation. Hot colors encourage students to become more physically active, while cool colors tend to convey a reassuring effect.” If you have not seen them personally, think about the school facility pictures you have seen where the paint is so old, dull, and peeled you cannot even tell what color it is. Sad to say, students affected by the achievement gap often are relegated to these rundown schools.

- Ample state-of-the-art technology for teachers and students makes a statistically significant contribution to student achievement.

It is impossible for the educator to know how teaching and learning will be influenced by technology in the future; however, are students in our less wealthy districts being afforded the same technological opportunities as students in the more wealthy districts? How can we expect the same outcomes without the same opportunities; i.e., computers to take home (iPads, Chromebooks, or other handheld devices), computer labs, and teachers knowledgeable about technology and how to use it as a learning and teaching tool?

These are only four of Tanner’s statistically significant findings. In total he identified twelve findings and fifteen best practices. All fifteen classifications in his research are postulated to have positive effects on student outcomes. I encourage you to read his research and ask yourself the question: Are your schools providing equal facilities to all children? Or, are there inequities that may contribute to the achievement gap?

As noted a few paragraphs ago, Marshall spoke of poor school facilities over four decades ago. He did not call it the achievement gap, but he spoke of opportunities lost and talents wasted. We can debate how to solve the problem, and discussion is needed. The school facility, however, is a “fixable” component of improving student achievement. Why are so many schools districts across the nation not enabled to improve the places where our students learn—especially for the minority and low-income students most affected by the achievement gap?

References and Resources:

Ballenger, K. A. (2014). The grave disparities in modern education, segregation, and school budgeting: A comparison between Brown v. Board of Education and San Antonio Independent School System District v. Rodriguez. Knoxville, TN: Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange.

Lacoe, J. (2013, March). Too scared to learn? The academic consequences of feeling unsafe at school. New York: Institute for Education and Social Policy (IESP). Retrieved on August 7, 2015 from http://steinhardt.nyu.edu/scmsAdmin/media/users/ggg5/Working_Paper_02-13.pdf

Martorell, P., McFarlin, Jr., I., & Stange, K. (2014, December). Investing in schools: Capital spending, facility conditions, and student achievement. Retrieved from Federal Reserve Bank of New York on August 7, 2015: http://m.newyorkfed.org/research/education_seminar_series/Stange.pdf

Service Employees International Union. (n.d.). Falling further apart: Decaying schools in New York City’s Poorest Neighborhoods. Retrieved on August 7, 2015: http://www.seiu32bj.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/falling-further-apart1.pdf

Smith, C. D. (2014). Continued disparities in school facilities: Analyzing Brown v. Board of Education’s singular approach to quality education. Tennessee Journal of Race, Gender, & Social Justice, 3(1), p. 38-66.

Tanner, C. K. (2015). Effects of school architectural designs on students’ Accomplishments: An meta-analysis. Retrieved from the Education Facilities Clearinghouse (EFC) on August 17, 2015: http://www.efc.gwu.edu//library/effects-of-school-architectural-designs-on-students-accomplishments-a-meta-analysis/

Vincent, J. M., & Filardo, M. W. (2008, June). Linking school construction investments to equity, smart growth, and healthy communities. Retrieved from Center for Cities & Schools (CC&S) and Building Educational Success Together (BEST) on August 7, 2015: http://citiesandschools.berkeley.edu/reports/Vincent_Filardo_2008_Linking_School_Construction_Jun2008.pdf

Linda Lemasters, Director, Education Facilities Clearinghouse

Linda is an associate professor in the Graduate School of Education and Human Development of the George Washington University, where she advises students, directs student research, and directs a project at Taibah University in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Her areas of expertise and research include educational planning, facilities management, and women CEOs. She actively conducts research concerning the effects of the facility on the student and teacher, publishes within her field, and has written or edited numerous books including School Maintenance & Renovation: Administrator Policies, Practices, and Economics and book chapters including a recent chapter, Places Where Children Play, published July, 2014 in Marketing the Green School: Form, Function, and the Future.