Tag: 21st Century

Planning for 21st Century Learning Spaces

T. R. Dunlap

Conversations on the development of 21st century learning spaces highlight the important role of planning in creating environments that maximize student learning. School systems across our nation routinely develop multiple types of plans—strategic plans, site-based plans, school improvement plans, capital improvement plans, and short-term planning initiatives. Planning is a crucial element for the success of any school system, and careful planning for flexible, innovative, and effective classrooms is imperative.

There are many important components in developing effective plans: beliefs, mission, parameters, strengths, weaknesses, organizational design, competition, external analysis, critical issues, objectives, strategies, and priority actions (Cook, 2001). As educational planners consider 21st century learning environments, they must remember that these spaces are instrumental in carrying forward the values and purposes of the community and district. Educational planning does have its challenges: inadequate funding, lack of commitment, and the inflexible nature of plans (Hambright & Diamantes, 2004). However, where plans are thoughtfully designed and carefully implemented, students, parents, teachers, and school leaders see numerous positive effects.

Many in the education sector would identify 21st century learning spaces as a planning priority for school systems. While districts devote great energy in developing high quality plans, the particulars of classroom design are often left to the site-based plans of individual schools. We know that the quality of a site-based plan can lead to positive implementation outcomes (Strunk, Marsh, Bush-Mecenas, & Duque, 2016). Consequently, planning for 21st century learning spaces must be a priority in our carefully crafted site-based plans. Planning for 21st century learning spaces must incorporate a number of considerations, especially the instructional aims of teachers.

Creating effective 21st century learning spaces that support a wide-range of instructional practices requires a great deal of foresight, deliberation, and action. We must look at what teachers are doing (or want to do) in their instructional spaces and design or retrofit classrooms to accommodate these teaching strategies. Many instructional options today are dependent on spaces such as outdoor classrooms, makerspaces, and multipurpose rooms. Teachers rely on access to technology, and they should be able to arrange their spaces in numerous configurations to support their instruction. Therefore, educational planners must consider the number of instructional approaches teachers utilize when developing facility plans for districts and schools. Ultimately, our purpose for developing 21st century learning spaces is to impact positively learning outcomes for students.

Schools have a tremendous opportunity to demonstrate a commitment to developing learning spaces that support the many needs of students and teachers. Accordingly, the need to develop 21st century learning spaces in a school’s planning process should not be ignored.

References:

Cook, W. J. (2000). Strategics: the art and science of holistic strategy. Westport, Conn.: Quorum Books.

Hambright, G., & Diamantes, T. (2004). Definitions, Benefits, and Barriers of K-12 Educational Strategic Planning. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 31(3), 233–239.

Strunk, K. O., Marsh, J. A., Bush-Mecenas, S. C., & Duque, M. R. (2016). The Best Laid Plans An Examination of School Plan Quality and Implementation in a School Improvement Initiative. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(2), 259–309.

T. R. Dunlap is a research associate for the George Washington University in the Education Facilities Clearinghouse. After having worked as a foreign language educator, he now researches topics relevant to education facilities and their improvements.

Designing Classrooms in the 21st Century: How New Instructional Methods Affect Learning Environments

By T. R. Dunlap

Trends in K-12 classroom design are currently undergoing revitalization as new teaching and learning models become increasingly popular. While many students are still stuck in rows of hard seats that face a board and a teacher, there are current classroom models that integrate time-tested, effective pedagogical practices with more recent trends in education research. Today, popular instructional approaches are serving as a driving force to conceptualize differently the designs of learning environments.

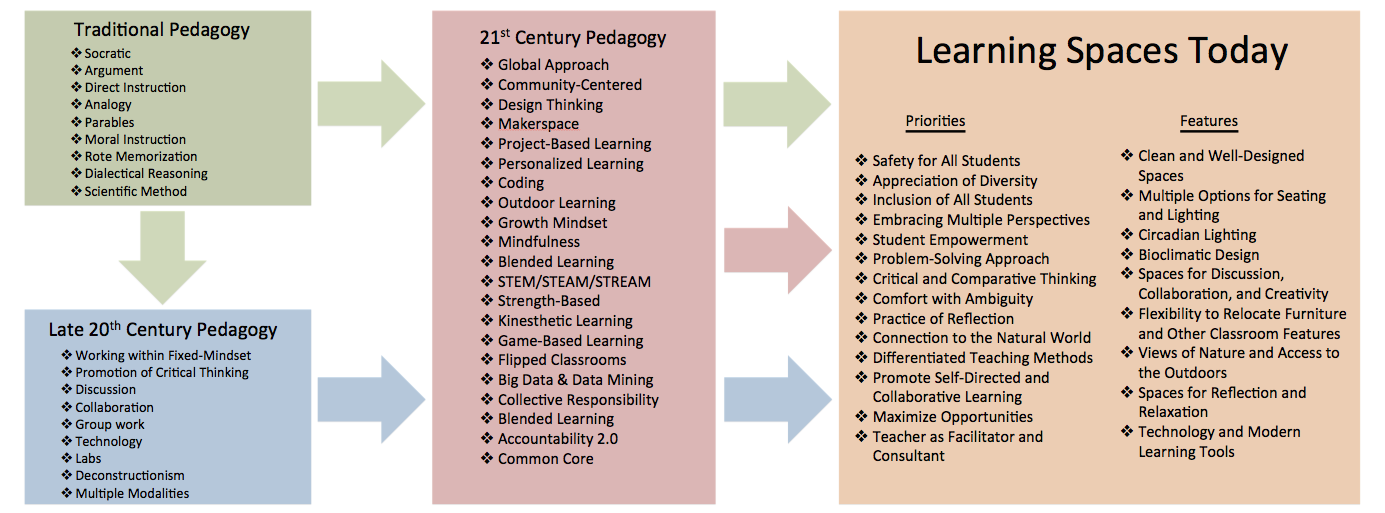

Traditional pedagogies have tended to involve direct instruction—teachers told students what and how to think. Classroom instruction has long employed strategies for listening, memorization, argument, dialectical reasoning, use of analogies, and moral thinking. Pedagogy has been principally a verbal exercise and has long required student to speak and write. Under traditional pedagogical practices, classrooms featured a teacher at the center or in the front of the learning space, a lectern, and rows of seats or desks—the elements of these classrooms were arranged for a teacher-centered instructional method. This model of the learning space has endured, relatively unmodified, for centuries.

By the late 20th century, educators shifted their philosophical approaches to teaching and learning, and they came to emphasize pedagogical methodologies that centered on deconstructionism, collaboration, and critical thinking skills. Consequently, learning spaces were outfitted to promote these instructional approaches. Classrooms would hold moveable desks to form collaboration teams, circular tables to facilitate discussions, and labs for scientific investigation. Learning spaces began to feature technology—perhaps a row of computers at the back of the classroom or a projection systems to display students’ presentations. It is impossible to underestimate how the use of technology fostered changes in how we conceptualize teaching and learning. At this time, the role of the teacher began to take a new shape, as well. Teachers became facilitators of instruction, guides to the curriculum, rather than the soul source of information. The role of the student also changed, becoming more active participants in the learning process.

Now, in the 21st century, conceptualizations of effective instruction have undergone a philosophical shift, again, taking on new identifying characteristics. Today, recent trends in instructional research have revolutionized the education sector, providing new language for teaching methodologies and supplanting old pedagogical practices for new ones. Forces of globalization and an increasing value placed on diversity and inclusion now guide our approach to teaching and learning. The education sector is now dominated by language to describe comparative thinking, design thinking, project-based learning, game-based learning, strength-based learning, personalized learning, collaborative learning, blended learning, kinesthetic learning, and outdoor learning. Our instructional methodologies involve the facilitation of growth mindsets, mindfulness, and reflection. We are routinely introduced to new priorities such as the STEM/STEAM/STREAM evolution, and we find ourselves implemented the newest teaching trends such as flipped learning, maker education, and the emphasis on coding.

As pedagogical practices evolve, we encounter a redefinition of our values, priorities, and conceptualizations of the teaching and learning processes. Today, our instructional trends aim for student outcomes that demonstrate effective communication, bolster abilities to access and analyze information, and promote adaptiveness. Schools today are a community-centered enterprise that fosters students’ physical, social, emotional, and intellectual development through employing the constructive instructional methods.

Now we must ask the question: In light of the many pedagogical development, what should modern learning spaces look like?

In order to approach the question of what modern classrooms should look like, we should consider identifying our instructional priorities, then engaging in a process of brainstorming the classroom features that best facilitate our aims. For example, a list of priorities might determine that classrooms should be safe, comfortable, flexible, and provide students a range of sensory experiences. We would want to develop spaces that allow for individual work, and promote collaboration. Our priorities should entail inclusion of all students, diversity, maximizing opportunities, and student empowerment. As we list our priorities, we can begin the process of developing a list of classroom features that would bring about the kinds of instructional experiences we desire.

The instructional evolution demands a reconceptualization of learning spaces in the 21st century. There are many ways to address remodeling and redesigning classrooms to incorporate effective elements of new pedagogical approaches. Imagine a learning space that promotes the appreciation of cultural diversity with displays of artifacts or live video streams to classrooms abroad. Think about a classroom that offers students opportunities to discuss English literature and philosophy over coffee and tea—just as coffeehouses provide a particular atmosphere for business professionals to converse and collaborate, so too could our students benefit from this type of space. Perhaps a learning space could promote meditation and relaxation with yoga mats and ambient music—students’ physical and emotional health and development would be positively affected by opportunities to disengage from the rigors of curriculum material for times of reflection. Maybe the classroom could be inside of a yurt or wigwam to allow students greater interaction with nature and to make science come alive. Learning spaces could be designed to bolster students’ sleep cycle with circadian lighting throughout the day, or feature a variety of seating options for comfort and to promote positive attitudes toward learning.

There are all sorts of ways we can design and adapt learning spaces to accommodate the changes in instructional research and new pedagogical methodologies. Long gone are the traditional, teacher-centered approaches to student learning. We must now accept that the models for effective pedagogy are multi-faceted and require spaces that allow for and support a plurality of instructional strategies.

Equipping School Leaders to Make the Most of Their Learning Environments

by T. R. Dunlap

Last week the National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP) had its annual conference in Kissimmee, Florida. Educational leaders from across the country gathered together at a beautiful resort for workshops on many topics facing public middle and high schools.

The event featured presenters who are on the cutting edge of educational research and administrative practice. Staff members from the Education Facilities Clearinghouse (EFC) were also in attendance. The EFC conducted a workshop on how school leaders can engage their communities by developing teams to conduct site assessments and to create emergency operations plans. These approaches to addressing school safety are critical. A number of the workshop attendees indicated that, as school administrators, they would make specific changes to their site assessment and emergency planning process as a result of the workshop. We at the EFC were very encouraged to know that these educational leaders will take steps to bolster the safety of their facilities and retool their operational planning for emergencies.

At this national conference, it was terrific to see school leaders gather together to address collaboratively the pressing issues schools encounter and to develop constructive ways to improve secondary education in this country. We must keep in mind how valuable organizations and conferences are to equip and enable leaders to do their jobs effectively. However, many school leaders cannot attend a professional conference or participate in a workshop with their peers. What resources are available for them? How can we ensure that all school leaders have the tools and resources available to make the most of their schools?

The EFC is here to help! We can come to your school. The EFC provides workshops for school leaders and staff at no cost. Learn more about the workshop opportunities we can provide your school for free.

At the recent national conference, many principals were curious about the free consulting services the EFC offers to improve public school facilities. The EFC works with schools across the United States to provide free technical assistance to make them a more safe, energy efficient, and clean space that fosters innovative teaching and learning. For more information on how the EFC can come to your school, watch this brief video.

Many school leaders identify facility needs as a top priority to improve the educational experience of their students. The mission of the EFC is to equip school leaders to make the most of their learning environments. The resources we provide to schools are indispensable. If you would like to discuss ways that we can help your school, contact the EFC today.

Effects of School Architectural Designs on Students’ Accomplishments: A Meta-Analysis

By C. Kenneth Tanner, 2015.

Architectural scholars have called for a complete working alternative to existing ideas about architecture in general. Since 1997 the School Design & Planning Laboratory has sought a similar alternative for school architecture, including the total educational environment, and worked persistently toward this goal. Hence, the objective of one primary cluster of SDPL research was to extend innovative ideas of these highly respected scholars to the field of educational architecture. Findings from the body of research, as discussed in this document, have also been interlocked to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs pyramid. The purpose for effecting this association was to guide how we think about the physical environment’s capacity to motivate individuals, especially students in school environments.

Taking the First Steps into 21st Century Learning: It’s more than just handing out iPads

By Greg Smith, Project Manager, Brailsford & Dunlavey, and Dr. Debra Henson, Executive Director of Facilities Management, Dekalb County School District.

Planning for the future is often done in a rear view mirror we plan based on what we know and create based on our own personal experiences, education, and expectations. So how can we, as educational facilities leaders and professionals, create an environment that delivers education in a way that resembles real world learning/working environments as they exist now and as they will exist in the future? The need to prepare students for a workplace that no longer operates in an industrial economic fashion, as it once did, is critical in order to ensure the next generation is ready for a new economy and workplace. As we enter this transformational phase in K-12 education and strive to prepare students for this new reality, we are challenged to determine the most beneficial capital improvement investments that incorporate new 21st century learning components.

American schools, designed around a standard learning environment that supports a lecture style of teaching, have remained relatively unchanged for the last 50 years while we have evolved into a society of visual and tactile learners. “Show me,” “interact with me,” “don’t just speak at me,” this is what our students ask of us. The critical components of learning that allow the modern student to effectively engage with educators and fellow students alike are the foundation for environments that encourage the four C’s: critical thinking, creativity, communication, and collaboration. This new model of education that focuses on engaging with students in a variety of ways is referred to as 21st century learning and the supporting facilities are 21st century learning environments.

Technology is often considered the catalyst for identifying 21st century spaces and its importance cannot be overrated. It is a tool, a resource that aids in the learning process and links real world platforms to PK-16 educational environments. But it is only a tool.

So what defines these 21st century learning environments? The words we most often use are flexible, agile, and adaptable, words that ultimately mean being able to adjust to new conditions, modify for a new use or purpose, and allow flexibility to engage students in a variety of ways. The 21st century learning environments respond, not react, to individual learning styles, teaching styles, and a variety of educational paradigms, including new Common Core standards. Educational facilities, similarly, need to respond to the needs of students, teachers, and community—form follows function—and provide a variety of opportunities for students to experience authentic interaction with real world involvement.

But how can we make informed capital investment decisions on adaptable learning environments? The practice of “evidence-based design” helps connect the relationship school facilities have with their impact on learning. As we continue to advance the research and examine what has been done in traditional schools and classrooms in planning and delivering 21st century learning, it will become increasingly imperative to understand the drivers responsible for different educational outcomes and create an effective physical framework for making capital improvement decisions that consider risk tolerances.

The Dekalb County School District (DCSD) is currently implementing construction of approximately $500 million in capital improvements under their special-purpose-local-option sales tax (SPLOST) IV Program. A primary focus of the program is how to best incorporate 21st century learning concepts into their facilities. One of the key challenges arising from this focus has been bringing its aging elementary schools into the 21st century while maintaining a balance with traditional education. DCSD is designing and constructing seven new prototypical elementary schools to replace some of the schools that are aged and in need of replacement. The project’s architect laid out some of the decisions made in order to achieve traditional education environments while also advancing their schools with new 21st century learning elements. He explained the three primary design decisions that the district made. First, they decided to incorporate 8-12 “flex spaces” that are smaller than classrooms and available for use in a variety of ways ranging from teacher meetings to student groups to specialized smaller learning sessions. These spaces will allow DCSD to maintain traditional classrooms as the primary learning environments while giving them the flexibility for collaborative learning or other uses, as needed. The second decision made was to incorporate an outdoor amphitheater in the prototype design. This option allows the schools to have outdoor classes, presentations, or group-based projects. And third, DCSD is currently working toward replacing the existing classroom furniture that combines the chair and the desk into one unit with separate mobile chairs and tables that allow teachers to be flexible in classroom set-ups. Rather than having student desks in rows for a lecture-oriented class, as is the case with the chair-and-desk combination unit, the new furniture can be set up in several ways to support different class activities.

America’s schools must continue to take these initial steps to evolve its schools and prepare students for the new economy. This, of course, means that facility planners must continue striving to identify drivers that produce the educational outcomes schools seek for their students, ones that help owners make informed capital improvement decisions to achieve a new targeted reality. There is much we continue to learn about transforming our K-12 schools into adaptable and flexible spaces and careful capital planning is as important now as it has ever been. Maybe more so.

Contact authors

grsmith@programmanagers.com

debra_henson@dekalbschoolsga.org

Brailsford & Dunlavey is a program management firm with comprehensive in-house planning capabilities, dedicated to serving educational institutions, municipalities, public agencies, and nonprofit clients from offices throughout the U.S.

Can This Building Teach About Sustainability in the 21st Century?

Marable, 2015

There are times when local education agencies (LEAs) go to their governing bodies for funding for school designs that include construction of a green school—a school that supports sustainable practices or has environmentally friendly facilities. While this type of construction can be supported in the research for reasons that include health, safety, and planet friendly practice, there often is little said about the instructional components of such facilities. This paper will explain how the components of green schools can enhance the implementation of environmental education curricula that help support 21st century skills. Currently, there is no set standard for the implementation of environmental education in green schools or for schools that utilize the building as a teaching tool for students. A recent study (Marable, 2015) was conducted in Virginia to help establish pedagogical best practices for environmental education, while describing how educators currently use LEED buildings as a teaching tool to support sustainable practices. The findings from the study indicated teachers employ practices that are consistent with current emphases on environmental education. Data also supported that educators take pride in their buildings and incorporate the facility as a teaching tool in a variety of instructional practices throughout the Commonwealth of Virginia.

The findings of this recent study and other relevant research explain and provide real examples of current environmental education practices being utilized to support 21st century skills within LEED certified schools. Examples of how the facility may be used as a teaching tool in environmental education are provided by school grade levels (elementary and secondary) and by building features in LEED construction.

Building 21: Designing a New Kind of High School

Building Schools for the Future Best Design for a New School

KELLAM HIGH SCHOOL REPLACEMENT: A Prototype for 21st Century Learning

Virginia Beach City Public Schools and HBA, 2015

This is a PowerPoint presentation descrbing this CEFPI 2015 National Award Winner.